Unemployment

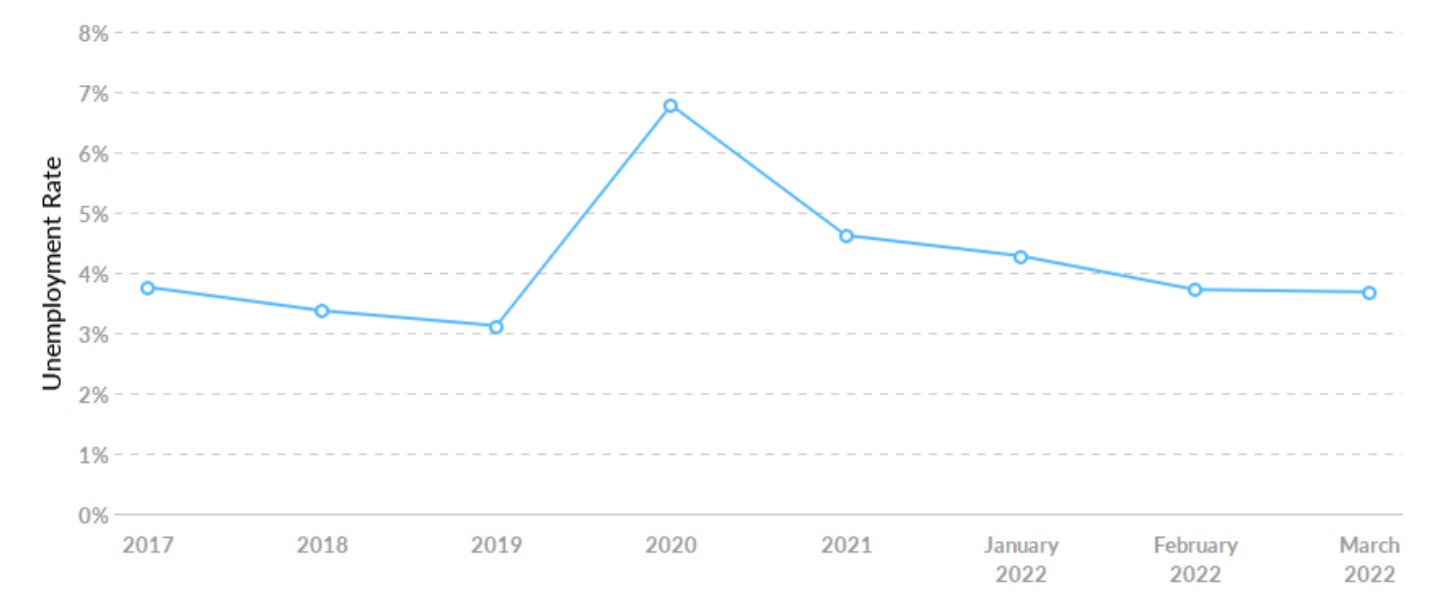

In St. Louis (like much of the US today), one cannot discuss labor without discussing unemployment. The pandemic has exacerbated racialized unemployment in St. Louis, which according to data from the Policylink/ERI National Equity Atlas from 2019 affected 12% of Black residents of the city of St. Louis and 10% people of color overall, while white residents had a 3% unemployment rate. Unemployment has a strong correlation to involvement with criminalized activities, as well as an over-burdening by fines, fees, and harassment. So too does unemployment deepen the divide on other indicators, including health and life expectancy. The clear impact of policing on workers supported the important decision to remove the St. Louis Police Officers Association from the St. Louis Labor Council. Even with the growing presence of tech companies and a geospatial hub, access to these opportunities is stunted due to a lack of workforce development pipelines. As one interviewee shared, “Communities that are hardest hit have no access to the education and training required to be engaged in those growth industries,” not to mention the ways that status quo racialized hiring can persist if there are no real mechanisms to challenge them inside a company.

The Fight for $15 and an Equitable Future

Those residents who can find work often find themselves in the rank of the “working poor,” receiving barely below 200% of the federal poverty line; this particularly hits Black workers hard at a rate of 17%, as well as Latinxs at 16%, while white workers were only 7% of this income bracket. Interconnected labor, faith-based, and neighborhood movements have sustained a concerted effort to challenge the ways in which the jobs that exist perpetuate racial and other inequality in St. Louis. Building from a longer history in the Fordist era of union power, some labor organizations have pivoted to directly address racialized wage inequality through the Fight for 15. At the center of this struggle have been mostly Black women in the fast food industry who helped launch this campaign in 2012, and have brought together groups like SEIU, Missouri Jobs with Justice, and others. The long, protracted struggle for a higher minimum wage began with a local ordinance that workers secured in 2015, only to be pre-empted by the Republican legislature. Pre-emption has been a major source of frustration in general for grassroots movements, who have seen progress upended by an overzealous conservative state that has stopped everything from paid leave to gig work restrictions to plastic bag bans.

Undaunted, workers took the fight to the state itself, with organizations like SEIU and others winning a 2018 statewide $15 minimum wage (even in a midterm election year). The victory showed the tremendous need but also the kinds of transformational movement relationships building between new generations of labor and community groups. Increasingly organizations like the Movement for Black Lives have also shifted this labor conversation and helped influence efforts like the “Show Me $15 and a Union” to accelerate implementation of the wage change. With such campaigns, worker-leaders have also made clear in new organizing that the minimum wage is just a first step, and that real worker voice means unionizing the sectors that now define St. Louis, including food service and healthcare. Workers have sought to take on paid leave as well, with more than 600,000 workers without paid leave in the state, per one interviewee. While the St. Louis economy moves through new phases and shifts, and community intervenes to shape that agenda, worker organizations and allies are making significant strides to establish a baseline for all workers who sustain the region.

Looking to Logistics and Living Out Racial Justice

Worker organizing is also moving with the times to new sectors that are becoming core to the regional economy, which are relying upon Black, Latinx, and migrant labor, and require a lens to include semi-rural exurbs of St. Louis. One such project is a growing warehouse worker organizing effort, spearheaded by the Missouri Workers Center. Fast food workers have led the way for this new precariously-positioned sector to also begin to organize, and are linked via the Worker Center, which has centered an anti-racist platform in its efforts. These speak to the promise of new, transformational alliances that first and foremost, are focusing on “developing worker leaders” who practice storytelling and finding ways to bring white workers to the fight against racism. This is being matched with more sectoral research on the industry and where gains are possible. Histories of organizing in the region show if St. Louis’ unions further take the lead from Black-led organizers and center countering the deeply entrenched racial segregation that has marked St. Louis’ economy, the possibilities to more rapidly shift course from a low-wage logistics sector to a high-road industry will become more real by the day.