Stemming from the longer history of rancher dominance and settler colonialism, the Inland Region’s city councils and county governments are dominated by older white residents tied to economic power. This has created a sense among some of those we spoke to of an “explicit exclusion” of communities of color by the institutions of power. Even where funding has been put from state projects towards local community engagement, these processes rarely involve trusted groups or proven ways of engaging diverse residents.

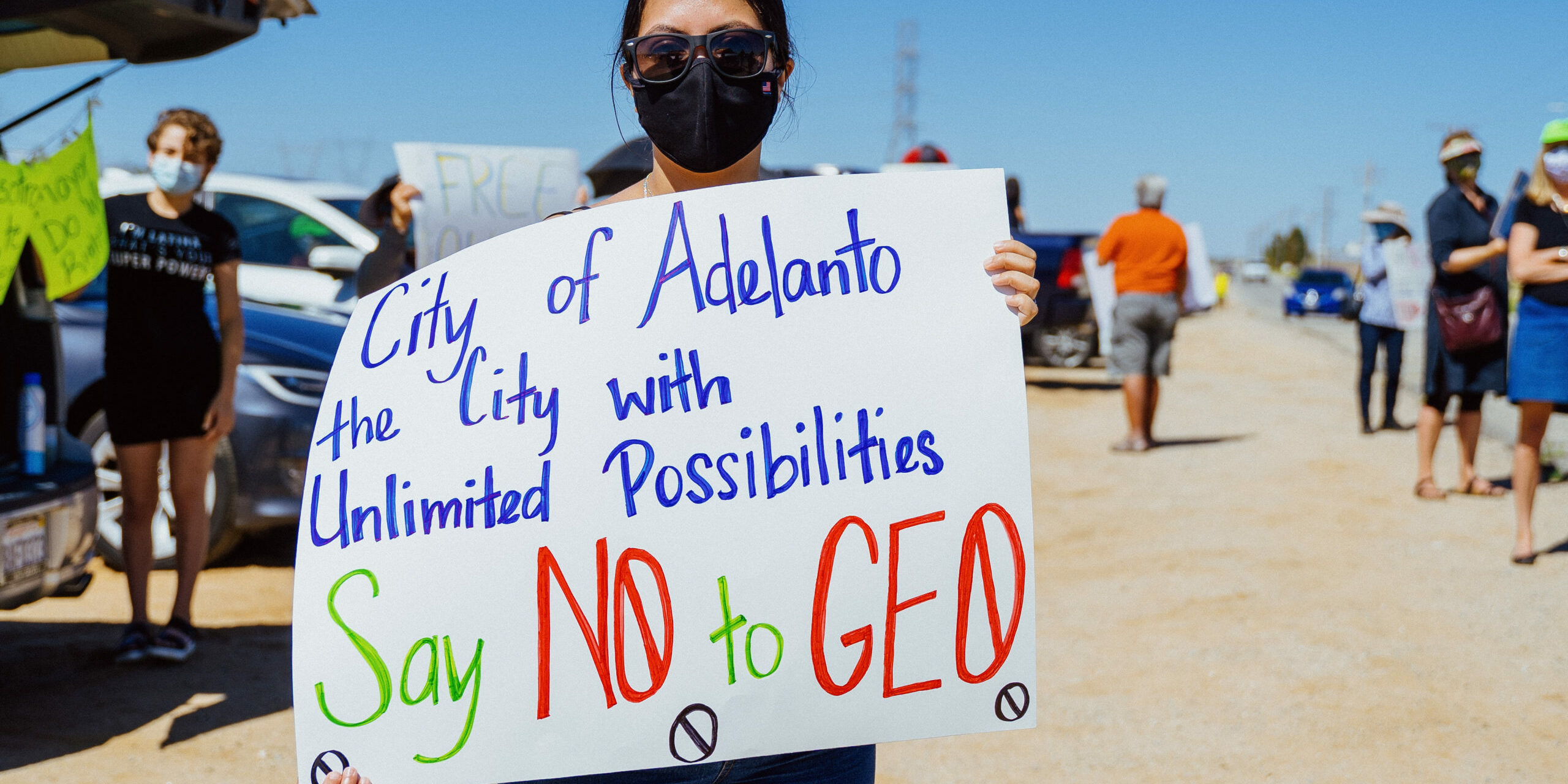

Strongly allied to conservative, entrenched power are police officer’s associations, like that of Riverside Sheriffs Association, which fund the District Attorney at 20 times the rate of any other DA in the country, as well as provide donations to Supervisor’s races. Prison guard associations and private prison groups have also held significant sway, such as GEO group, which has been shown to attempt numerous backroom deals in cash-strapped Adelanto to help keep its immigration detention facility open against state mandates. Developers have also become intimately involved in governance (and as noted elsewhere in this analysis, goods movement companies). Riverside County Supervisors’ unanimous approval of the luxury, million-dollar home Thermal Beach Club with a massive lagoon exemplified these patterns. The decision pleased developers but made no sense to local residents facing water tainted with arsenic (and limited water altogether) or living in trailers, with few other resources. On the flip side, while funding moves to police, prisons and mega-developments, residents in areas of Eastern Coachella and other rural areas must wait years for infrastructure projects.

Young leaders have taken up the challenge to transform these dynamics, such as Ben Reynoso, who ran and won to be the councilperson for San Bernandino’s 5th Ward. Endorsed by the Inland Empire Labor Council and other labor groups, Reynoso’s campaign has focused on inclusive development, educational access, and environmental justice and health access - all of which involve challenging the status quo power of goods movement. Change has been visible: in 2010, only 1 of 10 county supervisors was BIPOC; in 2021, the number shifted to 3. This has only been made possible by deep and long-term engagement to increase voter registration (noted in Movement Infrastructure).

One area where shifts have happened more rapidly is in state legislature representation. Spurred by broader efforts in California to scale up movement power to the state, organizations in the 501(c)(4) space have been able to mobilize to elect more progressive state representatives. In general, with this overall transformation at the state level, community groups seeking to hold goods movement companies accountable or to enact environmental justice legislation have found friendlier reception at the state level, even if it’s from electeds in adjacent areas (such as San Diego-area former representative Lorena Gonzales).