Temporary Growth, Permanent Stratification

While global billion-dollar logistics companies have sold a narrative of increased jobs and opportunities in exchange for tax breaks, the promises for a boom of jobs for the region rarely add up. According to data from the University of Redlands’ student-led, collaborative research, the average percentile for unemployment across census tracts with warehouses is 58% compared to the state average of 50%. The pandemic uptick in logistics - where as of 2021, one in eight Inland Region workers were employed in logistics - is in part because many of the other industries declined, such as hotels, arts and entertainment, recreation, and restaurants. Unemployment otherwise is still relatively high, and jobs are often of a temporary, low-wage nature - that risk entrenching intergenerational inequality.

Challenging this has been worker-led efforts, including a new movement in coordinated local union organizing. Both the Inland Empire Labor Council’s diverse leadership and the nascent Inland Empire Black Worker Center represent the kind of intersectional approach emerging. The IE Black Worker puts racial inequality at the center of an understanding of worker power, and also interlinks it to a dynamic workforce development pipeline through the new IE Works Program that provides equitable pipelines to public sector water infrastructure jobs. Drawing from its relationship to the SoCal Black Worker hub and knowledge of the value of pre-apprenticeship in addressing the kinds of historical inequalities affecting Black workers, this promising program is prioritizing those impacted by criminalizing systems and centering good jobs that also respond to the region’s lack of public infrastructure.

UFCW’s Local 1176 has moved in new directions, organizing cannabis workers and providing expungement services for workers affected by mass incarceration. IBEW, the Carpenter’s and other trades have become involved in Just Transition conversations. Healthcare workers with the USW and Teamsters have moved forward campaigns that have helped their wages advance to meet the realities of life.

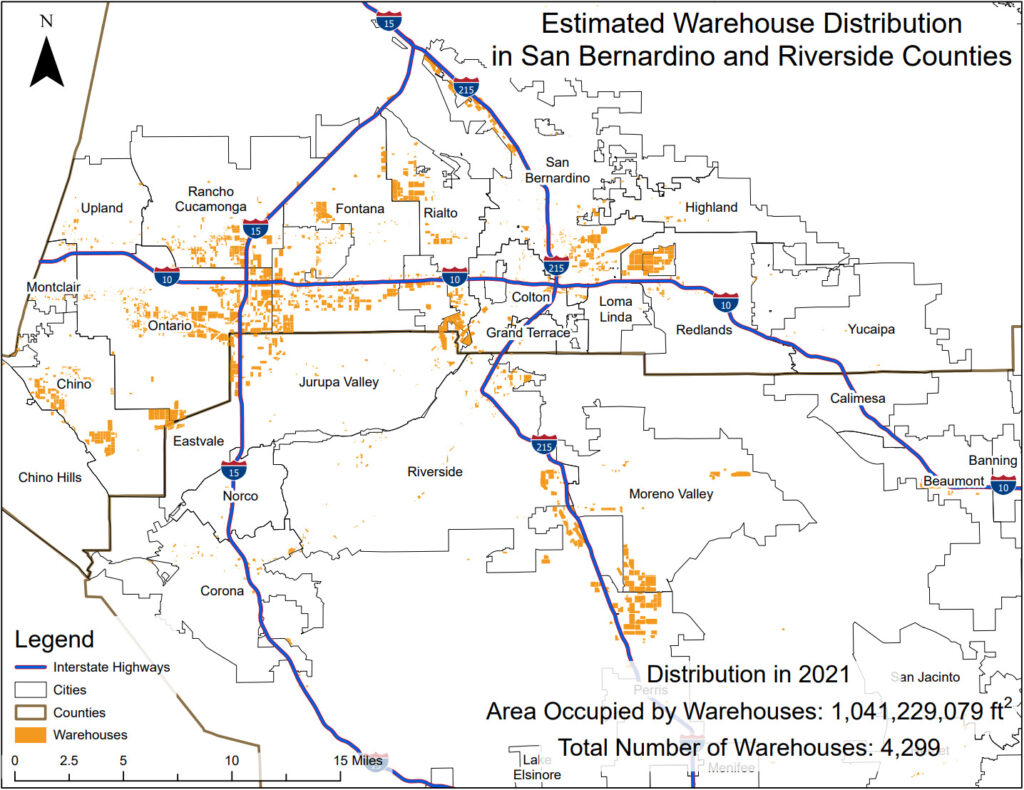

Logistics Industry

At the backbone of the logistics industry are thousands of low-wage, often Black and Latinx workers who provide the critical work that run the warehouses, trucks, trains, and behind-the-scenes movement of goods tied to the global economy. In an era where Amazon clocked more than $468 billion in revenue and $33 billion in profits in 2021, thousands of people operate round-the-clock at breakneck speed and with minimal protections. One of the key ways that companies have put pressure on workers is through setting quotas of processing items per hour (often 200 or more), reported through scanning devices that put workers at risk of performance reviews or firing and continually polices “time off task.” The high rates are part of what leads Amazon warehouses to have two times as many injuries as other warehouses, at a rate that has been rising consistently year after year. Such breakneck speeds have also affected drivers, who have been known to urinate in bottles to be able to make inhumane times set by the mega-company.

The Warehouse Workers Resource Center (WWRC), a worker-led space that offers education and organizing on issues such as wage theft, health, and compensation, has been at the forefront of the national movement for logistics workers. Their organizing brought to light the price of Amazon’s quotas, leading to Assemblymember Lorena Gonzales’ successful bill to give employees access to information about the quotas as well as built-in time for meals and restroom breaks. The commission also allows for greater transparency into worker injury data and quotas, and further paths for workers to organize against harmful work demands. The breakthrough organizing has also helped spur action from the federal labor regulators like OSHA, and in states such as Washington DC. WWRC has also secured $2.3 million for a high-road training partnership to set a model for apprenticeship that leads to better-paying, professionally-compensated and sustainable jobs in the field.

Hiding from Accountability

Part of the “innovations” of the logistics industry have been subcontracting services to 3rd and 4th party logistic companies, which are often essentially shell companies that work with the exact exploitative specifications demanded by Amazon or Wal-Mart. The 3PL/4PL structure shields companies from direct accountability, and many utilize temporary staffing to be able to keep a steady flow of workers in and out and evade any investment in benefits and health care. As one organizer shared, this has created “a density of low paying jobs and non-unionized labor, a cycle of temporary agencies, and [an economy without] long term quality jobs, which is seen as the most viable employment in the region.”

One of the ways organizers with Warehouse Workers Resource Center have fought companies’ efforts to avoid accountability is the “Warehouse Indirect Source Rule.” Implemented by the South Coast Air Quality Management District (SCAQMD), this requires warehouse operators to track the number and types of trucks that come to their door in order to calculate how much emissions they are creating. IBEW Local 11, which has supported green energy efforts, as well as other environmental and community-based groups came together with WWRC to achieve this important milestone. The warehouses will then be required to comply with emissions standards and respond by utilizing clean, green energy or paying emissions taxes. These have stood up to legal challenges and gained support from throughout the state and the country as a model to begin to regulate unchecked global logistics power, especially as they affect underserved communities like the Inland Region.